Viking Houses: How Vikings built their homes

Viking houses were adapted to the region and therefore built with the materials available in the immediate surroundings.

THE MAIN MATERIALS

PEAT

Peat is the oldest and most common building material, naturally insulating. It was used in Greenland and for 1100 years in Iceland, where the peat construction technique was so important that it has survived to the present day. Archaeological research of remains dating from the colonization of Iceland shows that the same types of peat were used to erect walls until the beginning of the 20th century.

The peat was removed by lifting the top layer of the ground or cutting it with a small blade spade. Used as 'bricks' to erect the walls or the roof, the different techniques depended on the type of peat required for the construction.

The sods used for the walls were called strengur (long grass strips) and hnaus (peat blocks), which divided themselves into different types, wedge-shaped blocks (klömbruhnaus) and regular blocks (kviahnaus).

WOOD

In Denmark, deciduous forests provided oak for framing, and hazelnut and willow to make the racks between each post supporting the walls. These woven wooden racks were then covered with a mixture of clay and dung (called "cob on racks") to make them watertight. In addition, the buildings inside the circular fortresses had strong log walls that required large quantities of oak.

Oaks are scarce in Sweden and Norway, except in the far south, so soft coniferous woods were used for construction. Long straight beams were placed horizontally on top of each other and notched so that they were firmly joined at the corners.

Roofs were often constructed with layers of turf as well, creating a natural green covering that blended the houses seamlessly into the landscape. This unique adaptation allowed Viking settlers in Iceland to build sturdy, warm homes despite the lack of native timber.

STONE

A stone foundation prevented the lower beams of the wooden house walls from rotting by insulating them from the damp ground. This foundation could sometimes support an interior floor of planks, which, when raised, provided additional insulation while also protecting the house from decay. The stones of the foundations, with the holes left by the wooden posts, are often the only remnants of Viking dwellings.

WOOD CONSTRUCTION TECHNIQUES

Several techniques could be used within the same construction.

Wooden walls could be built in different ways:

- half-timbered with clay fillings inside an oak frame,

with an alternation of horizontal boards and vertical beams,

- in standing wood,

- in intersecting horizontal beams and corners,

- in partitioning with clay and manure fillings.

Nails were commonly used to assemble wooden components.

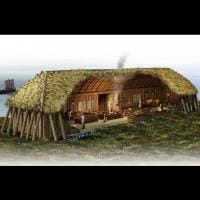

The roof was supported by 2 rows of posts that ran the entire length of the building. Sometimes, however, the posts were set back from the walls, supporting the ends of the roof rafters. This provided uninterrupted interior space and became the norm in the late Viking period.

A layer of birch bark on the frame often provided a seal. Roofing was made of thatch, grass or wood shingles.

PEAT CONSTRUCTION TECHNIQUES

In countries where wood is scarce, such as Greenland and Iceland, houses were built with blocks of peat, a naturally insulating material.

The walls were built directly on the ground without any foundation. The contours of the walls were delineated and, generally, peat inside the house was collected and then used to build the walls. Peat walls were generally 1 to 1.2 m thick.

Large stones or pebbles were placed along the inside and outside edges of the wall. Sods of peat and other stones were placed alternately on the inside and outside sides. Soil was used to fill the spaces between the layers.

At regular intervals, blocks of peat were placed perpendicular to the wall to solidify it. The upper section of the wall was built with wedge blocks and sod blocks between layers.

On the outside, a slight inward slope was applied to the wall so that it could better support the weight of the roof. On the inside, the wall tapered slightly to its mid-height and then tilted inward until the vertical lines at the top and bottom of the interior side joined.

The two principal types of frame were timber-beamed and rafter-roofed houses, both of which had several subcategories.

Roofing was generally made of three layers. Inside the house was peat with the grass side down and on top of which soil had been compacted, then a new layer of peat was laid on top, grass side up. It was also common to place small branches or twigs under the sod to prevent the rafters from rotting.

THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF HOUSES

The Viking house was usually a longhouse called a hall (skalar or eldaskáli) in the Icelandic sagas.

THE LONGHOUSE

The Longhouse was an independent building, varying in length from 10 to 38 meters on average and rarely more than 5 meters wide. But in Borg, on the Lofoten Islands, one of these buildings was 83 meters long and must have been the dwelling of a chief.

The Viking house was most often a farm that could accommodate between 30 and 50 people, the whole family and its slaves, working, eating and sleeping under the same roof.

Domestic animals were sheltered in a room at one end, providing an additional source of heat. In some cases, the number of animals can be estimated by counting traces of stalls in the barn.

One of the farms in the village of Vorbasse in southern Jutland, Denmark, housed fourteen large animals, probably cattle. Of the total length of 25m, 8 were thus reserved for the barn.

Its basic oblong shape, slightly narrower at the ends than in the center, with walls that were generally oblique or curved to resemble the shape of an overturned Viking ship, was identical and easily recognizable throughout.

The entrance was usually open near one end of the hall. Sometimes there were other doors, either forward or aft, also located at the ends of the building. These were wooden doors that could be locked, as early as the 11th century, by T-slot locks and specially shaped keys that opened the padlock by compressing a system of leaf springs.

A few tiny windows with bladder skins stretched over them could let some light in.

From the tenth century on, changes were made to the constructions in the form of enlargements, first of random size and style, then in a more standardized way. Thus the stable was separated from the main hall used as a dwelling. Eventually, the latter included a variable number of outbuildings, sometimes surrounded by a fence or a stone wall.

There were clusters of farms in the Viking Age, suggesting some form of communal organization. These villages seem to have been fairly widespread in Denmark, while in Sweden and Norway they were more likely to be isolated farms or small communities.

THE TOWN HOUSE

Very different architecture developed in urban centers like Hedeby [just south of present-day Schleswig in Germany, which was Danish until 1920], where water preserved the foundations and substructure of wooden buildings and the entire gable of a 5-meter high house. Hedeby was the largest city in Northern Europe in the Viking Age, and was home to the most sophisticated houses of the time.

The houses in Hedeby were rectangular, about 12 meters long and 5 meters wide. The walls were made of vertical posts and rafters filled with cob, supported by sloping exterior posts. The interior was also different, with much less space available, but the houses built higher up included a floor probably dedicated to sleeping.

THE PIT HOUSE

A pit house is a half-buried house about 1 meter deep in the ground. It was often only 3 to 4 meters long and 2 to 3 meters wide. Because the excavated earth formed the lower part of the walls, the house naturally benefited from the insulating properties and, to some extent, the heat of the ground. This type of building could be erected quickly and required little building material.

Whether it was because of the low cost of construction, or because of the lack of available materials, as in Greenland, it seems that pit houses were the preferred habitat of the poor.

Near the longhouses, the vestiges discovered by the archaeologists indicate that they were used as weaving or pottery workshops as in Sædding (Denmark), as a forge, as stables for small livestock or even as houses for slaves.

But there are also large complexes composed solely of pit houses, such as at the site of Löddeköppinge (Skåne, Sweden), where they are said to have housed merchants who lived there only during certain periods of the year.

The pit house was almost completely abandoned after the Viking Age.

VIKING HOUSE INTERIOR

The house's interiors were quite the same throughout Scandinavia.

An entrance hall gave access to the central part of the building. The term eldaskáli seems to refer to this central room.

The main room that served as a dwelling was rectangular in shape and of varying dimensions. According to the architecture (see above), two rows of solid posts supporting the roof could delineate two parallel spaces.

The floor was generally made of rammed earth, very rarely a floor.

In the center of the inhabited part was the hearth, the "long fire", a simple hole dug in the earth, sometimes built and cemented with mud or delimited with stones, which provided heat, light and means of cooking. There was no chimney, the smoke escaped through a hole in the roof.

On each side, benches ran along the walls. These were usually earthen embankments covered with a wooden frame that served as seats during the day as well as beds for the night.

Crosswise partitions sometimes divided the house into several rooms, which could be used mainly as storage and work space. A separate kitchen, for example, was unusual.

FURNITURE AND INTERIOR DECORATION

Most of the information concerning Viking household objects and furniture comes from the funerary furniture discovered in burials that are often those of wealthy people. It is likely that the more modest interiors contained only rare furniture.

Everything the occupants owned, from clothing, tools, kitchen utensils, and games to furniture and the house itself, was made and built by them. Only a few items may have been supplied by itinerant craftsmen or purchased in cities in exchange for farm produce. Imported luxury goods were mostly reserved for cosmopolitan urban populations.

Most of the furniture that has been recovered is stools and chests closed with a latch or a mechanism similar to a padlock.

The best preserved furniture comes from the large princely tombs of Oseberg and Gokstad in Norway, dated to the 9th and 10th centuries. Among them, a bed with uprights carved with dragon heads, a chair with a woven seat, several chests often decorated, a large number of tools and instruments for working with wood, and large, richly decorated buckets that could have been used for brewing beer or containing salted meat. A smaller bucket, closed by a lock, contained weaver's tools.

In a rich Danish tomb there were still fragments of a small wooden table, the top of which was a sort of slightly hollowed-out bronze dish that may have served as a dressing table. The usual tables of the Vikings must have had the aspect of all those of the Middle Ages, long and narrow, such as those represented on the Bayeux Tapestry.

In the dwellings which were set on fire, it was possible for the researchers to locate the place where the loom was located thanks to all the weights fallen on the ground.

The benches and the beds were provided with heavy covers of which fragments were discovered in the burial of Oseberg. Remains of feather pillows have also been identified at various archaeological sites.

The cauldrons, suspended by chains above the hearth, were made of riveted iron, copper sheets, or cut out of soapstone which is easily hollowed out and retains heat for a long time. The latter must have been the most prized because they are the most commonly found during excavations.

LIGHTING

In addition to the light from the fireplace, the house could be lit, if necessary, with softwood torches.

The most important and widespread source of light, both in the city and in the countryside, was the stone, ceramic or metal oil lamp.

Wax candles only appeared with the conversion to Christianity towards the end of the 10th century. However, since beeswax resources were limited, tallow candles were more common.

DECOR

There is little information about interior decoration. Some furniture had to be painted. Chemical analyses have detected the presence of pigments of different colors (white, red, green, black and yellow) on wooden objects unearthed by archaeologists in the burial chamber of King Gorm the Elder in Jelling.

The richest interiors were embellished with engravings and carvings made on the posts and door jambs, as well as with tapestries, like the one discovered in the Oseberg tomb-ship, or with frescoes.